Detecting vandalism in OpenStreetMap – A case study

by Pascal Neis - Published: June 18th, 2017

This blog post is a summary of my talk at the FOSSGIS & OpenStreetMap conference 2017 (german slides). I guess some of the content might be feasible for a research article, however, here we go:

Vandalism is (still) an omnipresent issue for any kind of open data project. Over the past few years the OpenStreetMap (OSM) project data has been implemented in a number of applications. In my opinion, this is one of the most important reasons why we have to bring our quality assurance to the next level. Do we really have a vandalism issue after all? Yes, we do. But first we should take a closer look at the different vandalism types.

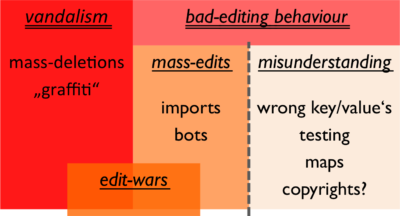

It is important to distinguish between different vandalism types. Not each and every unusual map edit should be considered as vandalism. Based on the OSM wiki page, I created the following breakdown. Generally speaking, vandalism can occur intentionally and unintentionally. Therefore we should distinguish between vandalism and bad-map-editing-behavior. Oftentimes new contributors make mistakes which are not vandalism because they do not have the expert mapper knowledge. In my opinion, only intentional map edits such as mass-deletions or “graffiti” are real cases of vandalism.

To get an impression of the state of vandalism in the OSM project, I conducted a case study for a four week timeframe (between January 5th and February 12th, 2017). During my study I analyzed OSM edits, which mostly deleted objects from new contributors who created fictitious data or changesets for the Pokemon game. If you did not hear or read about OSM’s Pokemon phenomena, you can read more about it here. The OSM wiki page for quality assurance lists some tools that can be used for vandalism detection. However, for this study I applied my own developed OSM suspicious webpage and the quite useful augmented OSM change viewer (Achavi). Furthermore, a webpage that lists the newest OSM contributors may also be of interest to you.

So what can you do when you find a strange map edit that could be a vandalism case? The OSM help page contains an answer for that. First of all: Keep calm! Use changeset comments and try to ask in a friendly manner for the suspicious mapping reasons.

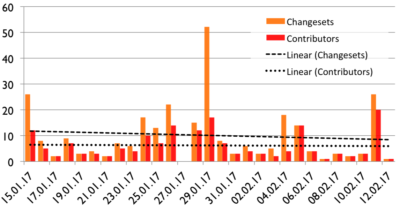

Results of the study: Overall I commented 283 Changesets in the aforementioned timeframe of four weeks. Unfortunately I did not count the number of analyzed changesets, but I assume that it should be around 1,200 (+- 200). The following chart shows the commented changesets per day. The weekends tend to have a larger number of commented/discussed changesets.

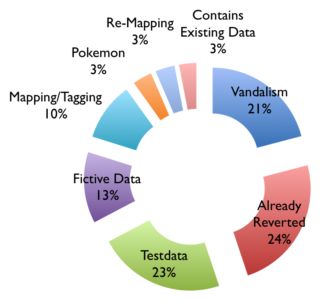

As mentioned in the introduction of the vandalism types, we should distinguish between different vandalism types. The following image shows the numbers for each category. In my prototype study, 45% of the commented changesets were vandalism related and 24% have already been reverted which was not documented in the discussion of the changeset. Sometimes I also found imported test- and fictitious data, which the initial contributor of the changeset didn’t revert. It should be clarified to everyone that the live-database should never be used for testing purposes. Interested developers can use the test API and a test database (see sandbox for editing).

Responses and spatial distribution: Overall I received 70 responses for the discussed changesets, sadly only 20 from the owner/contributor of the changeset. But, more or less every response was in a friendly manner. Most often the contributors wrote “thank you” or “I didn’t know that my changes are going to be saved in the live database”. Furthermore, if I received a response, it was within 24 hours.

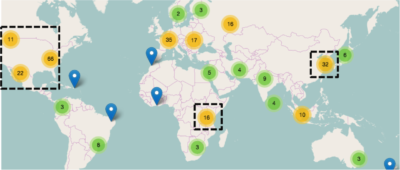

The following map contains some clustered markers. Each one highlights areas where the discussed changesets are located. As you can see on the map, the commented changesets are spread almost all over the world. In some areas they tend to correlate with the number of active OSM’ers. However, here is some additional information about three selected areas: 1: USA – Several cases of Pokemon Go related and fictitious map edits. 2: Japan/China – Some mass deletions and 3: South Africa – Oftentimes new MissingMaps or HOT contributors tend to delete and redraw more or less the same objects such as buildings. I guess it was not explained well enough to these editors that this destroys the object history? However, the article about “Good practice” in the OSM wiki is quite useful in this case.

Conclusion: The study reveals that there is an ongoing issue with vandalism in OSM’s map data. I think we do need to simplify the tools for detecting vandalism. In particular we should omit work where several users review identical suspicious map edits. Maybe the best possible solution should be a tool which is integrated directly in the OSM.org infrastructure. However, my presentation also contained some statistics and charts about the OSM changeset discussions feature. This will be the content of a separate blog post in following weeks. Also, the prototype introduced at the end of my talk will (hopefully) be presented in the next few months.

Thanks to maɪˈæmɪ Dennis.

thank you for your hard work in openstreetmap. also, if you could update the page http://resultmaps.neis-one.org/unmapped , cause it’s one year later and many places were mapped 😉

Hi erick,

thank you very much for your comment.

Just updated “Unmapped Places of #OpenStreetMap”. Have fun.

All the best,

Pascal

thank you for your hard work at openstreetmap. also, if you could update the page http://resultmaps.neis-one.org/unmapped , cause it’s one year later and many places were mapped 😉